AAPI History is American History: Revisiting Carry Them All

*Note – article mentions suicide

May comes to a close this week, and with it Asian American & Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month. This year, I’m reflecting on one big word from the month’s title – ‘American’ – by revisiting the title track from my album, Carry Them All.

Every year, this month teaches me something about the community and my place in it, and I discover something fresh to celebrate about being part of the AAPI diaspora.

In May of 2023, more than ever I saw a focus on the importance of AAPI Heritage Month as an opportunity to uplift AAPI heritage and history as AMERICAN history, in defiance of the the long, painful pattern of AAPI’s being treated as ‘forever foreigners’. One of the gifts of the mixed heritage experience is existing in these intersections and knowing this truth intrinsically, in your bones. For the sake of this story, I’ll define ‘American’ as capturing that ‘American Dream’ — an immigrant story and the struggle to create a better life for the generations after.

I Carry Them All in Me

“Carry Them All” is about two of my great-grandmothers, both immigrants, one from Ireland and one from China. What’s more American than the symmetry of these two women, of the same generation but both from opposite sides of the world, making new lives in the United States? The first verse paints the picture:

Had a chip on my shoulder since the day I was born,

Held by hands that worked, and were worn,

That were raised up by arms that weathered the storm,

I carry them all in me.

Got the blood of a dragon and the shape of her face,

These freckles a kiss, Emerald Island that made

A woman who drank, and laughed, and sang.

I carry them all in me.

Kat Keogh was my great grandmother from Ireland, and Lum Shee Chew my great grandmother from China. Both of their lives were incredibly hard, and I’m deeply aware that my own life and the independence and voice I have is only possible because of their sacrifice and their bravery. While Kat’s story is one for another day, let’s meet Lum Shee (better known as Popo, maternal grandmother in Cantonese).

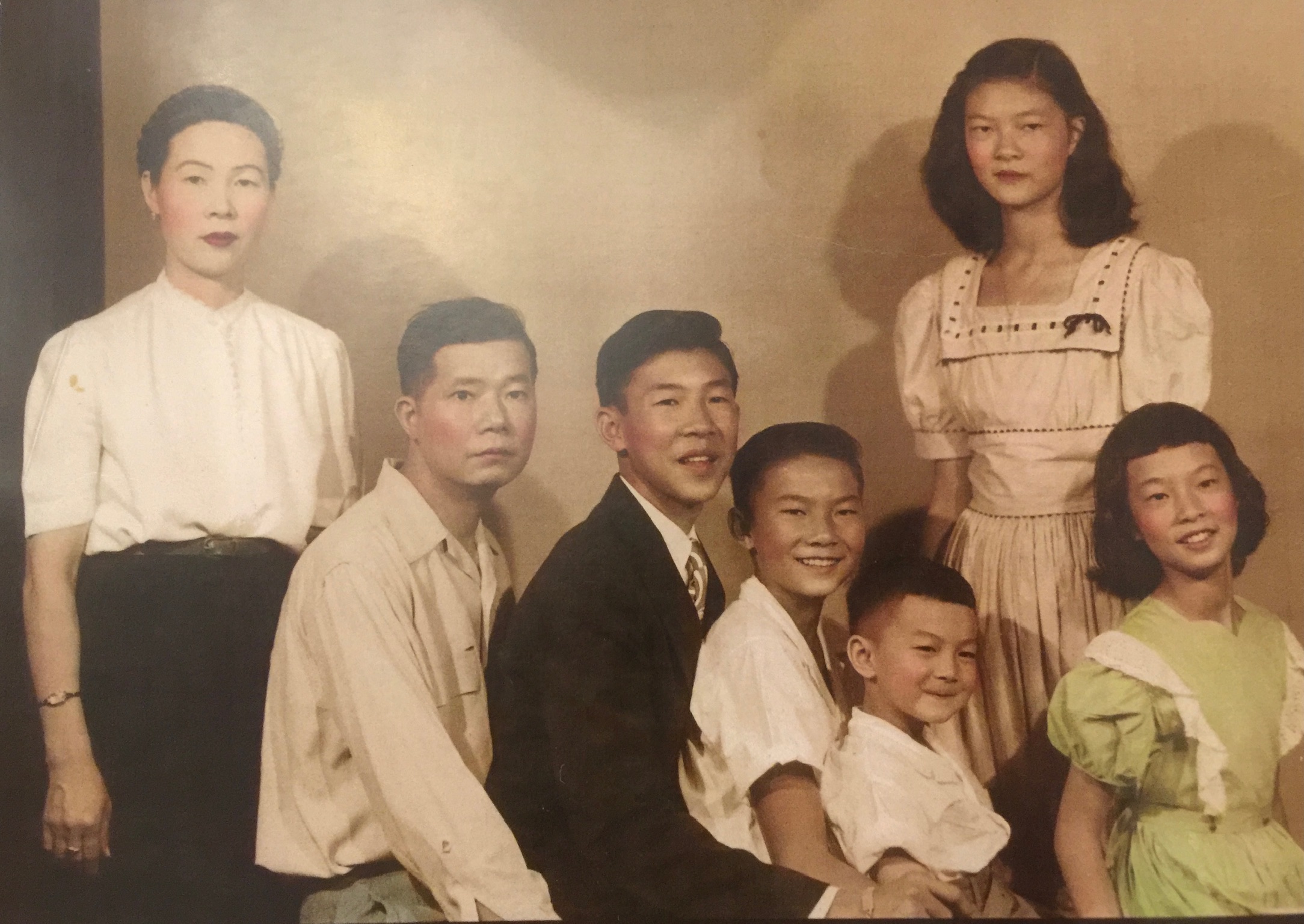

Meet Po Po, Lum Shee Chew

Po Po followed her husband, Quan Lung (or again, Gong Gong, maternal grandfather), to Atlanta from a small village outside Guangzhou, while the Chinese Exclusion Act was in place. They raised my grandma and four of her siblings in the back of their laundry (the eldest daughter, Ho, was left behind in China). She was both affectionately and not so affectionately referred to as the Dragon Lady; all painful associations with the stereotype aside, it fit. She was a little scary. She had to be. She ran much of the business through sheer force of will as Gong Gong, an artist at heart living with bipolar disorder before I’m sure any true help existed for him, did his best.

Po Po followed her husband, Quan Lung (or again, Gong Gong, maternal grandfather), to Atlanta from a small village outside Guangzhou, while the Chinese Exclusion Act was in place. They raised my grandma and four of her siblings in the back of their laundry (the eldest daughter, Ho, was left behind in China). She was both affectionately and not so affectionately referred to as the Dragon Lady; all painful associations with the stereotype aside, it fit. She was a little scary. She had to be. She ran much of the business through sheer force of will as Gong Gong, an artist at heart living with bipolar disorder before I’m sure any true help existed for him, did his best.

There’re endless nuggets of American history in their experience, to name a few:

- They lived and grew up Chinese in the Jim Crow South. The nuance of this experience in Atlanta in the 30’s and 40’s as a person who didn’t visibly fit into the Black/white binary is a fascinating and complicated chapter of history that I could never do fully justice to here (the documentary Blurring the Color Line paints the sometimes painful picture beautifully, and the wonderful historical fiction book The Downstairs Girl is worth a read. Both center around Georgia). The Chinese existed somewhere between Black and white, very much ‘other’, and while Po Po and Gong Gong washed clothes, between scampering around the laundry, the kids were raised by a nanny, a Black woman named Lucy, who they loved like a mother.

- Chew was their paper son name; back in China, our name was Jung.

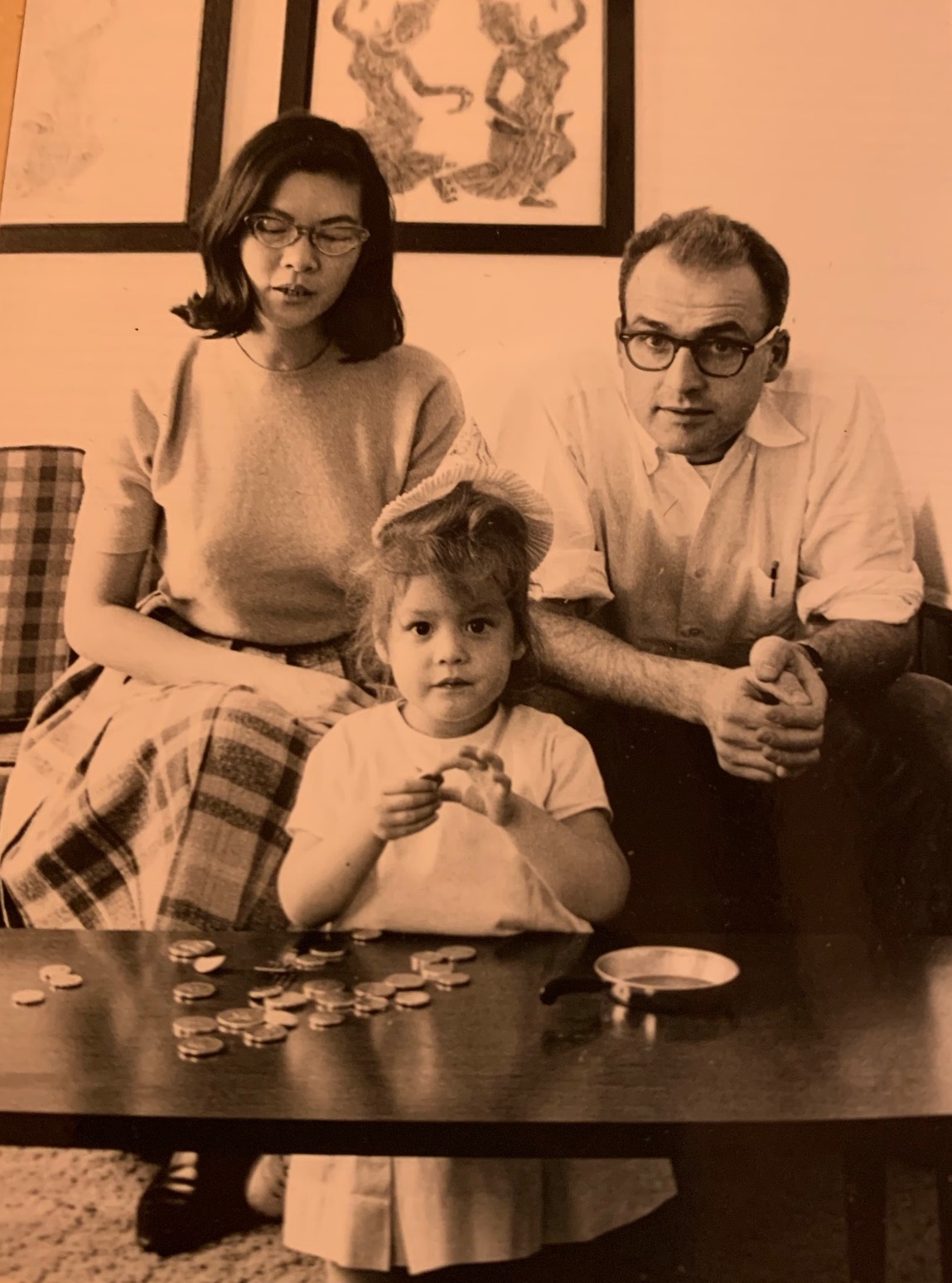

- When my grandparents wanted to get married in the late 1950’s, their marriage was still illegal in my grandma Soo’s home state of Georgia. Luckily they were already in San Francisco. My mom was already 6 years old when interracial marriage was legalized across the United States through Loving vs. Virginia.

Through it all, eventually, a little baby named Stephanie was born in Northern California, and Po Po got to spend her final days laughing at me and holding my chubby little feet.

Through it all, eventually, a little baby named Stephanie was born in Northern California, and Po Po got to spend her final days laughing at me and holding my chubby little feet.

I can only wonder what she must have felt to see the progression of her life until then. After Atlanta, she followed my grandma to San Francisco, and was close while my mom and aunt grew up. She reconnected with Aunt Ho after she was able to come to the US. She lost her husband to suicide when he walked off a pier into the Bay, and wailed at his funeral. She saw her children grow and marry and settle across the country from New York City to Honolulu, and now, she was playing with this little baby, that at once could look so unlike her and yet share the same round moon face as her daughter Soo. In all its grit and heartbreak and beauty, what a singularly Asian AMERICAN life it was.

An Asian American Life

Reflecting on these journeys in 2023, I feel pure luck and gratitude to live where I do on Gold Mountain/in San Francisco, in a city that has AAPI history and my own family’s history embedded in every stone, and pursue a life in music. It’s baffling when I think about it too much, and it’s an ongoing practice to transform the weight of it into inspiration to live my life in my own way. I firmly believe this is the best way to honor the sacrifices they lived, so that each subsequent generation requires a bit less of that sacrifice.

So I raise up my glass on March 17th,

and on Lunar New Year, I take to the streets,

I’m grateful their miles mean that my feet

Can carry it all in me.

To all of us reflecting on the very American stories of our families who happen to be of Asian American & Pacific Islander descent, and even those who aren’t, I leave you with some final lines of the song as a prayer of celebration and of the honor and responsibility that it is to be part of this long American history:

What does it mean to be a good ancestor?

I don’t think there’s an answer;

Just follow your heart so the rest can too.

You carry them all in you.